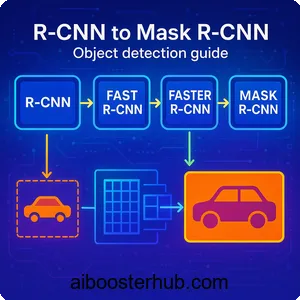

Large Language Models Explained: GPT, LLaMA, and Beyond

Large language models have revolutionized the field of artificial intelligence, transforming how machines understand and generate human language. From chatbots that can hold natural conversations to systems that write code and analyze complex documents, these powerful AI systems are reshaping our technological landscape. But what exactly are large language models, and how do they work? In this comprehensive guide, we’ll explore the foundations of LLMs, examine popular models like GPT and LLaMA, and understand the architecture that makes them so powerful.

Content

Toggle1. What is a large language model?

Understanding LLM meaning

A large language model (LLM) is a type of artificial intelligence system trained on massive amounts of text data to understand, generate, and manipulate human language. The term “large” refers to both the enormous dataset used for training and the model’s size, typically measured in billions of parameters. These parameters are the internal variables that the model adjusts during training to learn patterns in language.

At its core, an LLM is a statistical model that predicts what comes next in a sequence of text. When you type a message, the model calculates the probability of each possible next word based on the context of previous words. This seemingly simple task, when performed by a model with billions of parameters trained on trillions of words, produces remarkably human-like text generation capabilities.

The evolution of language models

Language models aren’t entirely new. Earlier generations existed, but they were much smaller and less capable. Traditional language models might have millions of parameters and be trained on relatively modest datasets. The breakthrough came when researchers discovered that scaling up both model size and training data led to emergent abilities—capabilities that smaller models simply didn’t possess.

Modern LLMs can perform tasks they weren’t explicitly trained to do, such as translating languages, answering questions, writing code, or solving mathematical problems. This versatility stems from their exposure to diverse text during training, allowing them to learn general patterns about language, reasoning, and knowledge representation.

How LLMs differ from other AI systems

Unlike traditional AI systems that are programmed with explicit rules, LLMs learn patterns from data. A rules-based translation system might have thousands of hand-coded grammar rules, while an LLM learns translation by observing millions of example translations. This data-driven approach makes LLMs more flexible and capable of handling nuanced, real-world language use.

Another key distinction is that LLMs are foundation models—general-purpose systems that can be adapted to many specific tasks. Rather than training a separate model for each task, you can fine-tune a single LLM or simply provide it with appropriate instructions. This efficiency has made LLMs the backbone of modern generative AI applications.

2. The architecture behind LLM models

The transformer revolution

Nearly all modern large language models are built on the transformer architecture, introduced in the landmark paper “Attention Is All You Need.” Before transformers, language models relied on recurrent neural networks (RNNs) or long short-term memory (LSTM) networks, which processed text sequentially, one word at a time. This sequential processing was slow and struggled with long-range dependencies—understanding how a word at the beginning of a sentence relates to one at the end.

Transformers solved these problems through parallel processing and a mechanism called attention. Instead of reading text sequentially, transformers process entire sequences simultaneously, using attention mechanisms to determine which parts of the input are most relevant to each other.

Self-attention mechanism

The attention mechanism is the heart of transformer architecture. When processing a word, the model doesn’t just look at that word in isolation—it considers the entire context by computing attention scores between that word and every other word in the sequence.

For example, in the sentence “The animal didn’t cross the street because it was too tired,” the word “it” could refer to either “animal” or “street.” The attention mechanism helps the model determine that “it” most likely refers to “animal” by computing high attention scores between these words based on learned patterns.

Mathematically, attention is computed using three learned transformations of the input: queries (Q), keys (K), and values (V). The attention output is calculated as:

$$ \text{Attention}(Q, K, V) = \text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^T}{\sqrt{d_k}}\right)V $$

where (d_k) is the dimension of the key vectors. This formula essentially computes how much each word should “attend to” every other word, then combines the value vectors accordingly.

Multi-head attention and layer stacking

Real transformers use multi-head attention, which means they run multiple attention mechanisms in parallel, each potentially focusing on different types of relationships. One attention head might focus on syntactic relationships, another on semantic similarity, and another on long-range dependencies.

These attention mechanisms are organized into layers, and modern LLMs stack dozens or even hundreds of these layers. Each layer processes the output of the previous layer, building increasingly abstract representations. Early layers might capture basic syntax and word relationships, while deeper layers understand complex semantic concepts and reasoning patterns.

Pre-trained models and transfer learning

The typical lifecycle of an LLM involves two main phases: pre-training and fine-tuning. During pre-training, the model is trained on a massive, diverse corpus of text using self-supervised learning. The most common pre-training objective is next-token prediction: given a sequence of words, predict what comes next. This simple task forces the model to learn rich representations of language.

After pre-training, the model can be fine-tuned on specific tasks with much smaller datasets. For instance, a pre-trained model might be fine-tuned on medical literature to become a specialized medical AI assistant. This transfer learning approach is far more efficient than training specialized models from scratch.

3. Popular LLM models and their characteristics

GPT: Generative pre-trained transformers

The GPT family of models, developed by OpenAI, are perhaps the most well-known large language models. GPT stands for “Generative Pre-trained Transformer,” which describes its three key characteristics: it generates text, it’s pre-trained on massive datasets, and it uses transformer architecture.

GPT models are autoregressive, meaning they generate text one token at a time, with each new token conditioned on all previous tokens. This makes them particularly strong at creative writing, dialogue, and any task requiring coherent long-form generation. The models use a decoder-only transformer architecture, which differs from encoder-decoder models like the original transformer.

The progression from GPT-1 to more recent versions shows dramatic scaling. GPT-1 had 117 million parameters, while later versions scaled to hundreds of billions. This scaling brought qualitative improvements: larger GPT models can follow complex instructions, maintain consistency over longer contexts, and exhibit reasoning capabilities that smaller models lack.

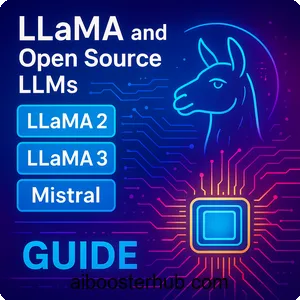

LLaMA: Large language model meta AI

LLaMA, developed by Meta, represents an important trend in open language models. While GPT models are primarily accessible through APIs, LLaMA’s weights have been made available to researchers, fostering innovation and transparency in the AI community.

LLaMA models are designed with efficiency in mind. They use various optimizations to achieve strong performance with fewer parameters than comparable models. For instance, LLaMA uses RMSNorm instead of LayerNorm for normalization, and it employs rotary positional embeddings (RoPE) instead of absolute positional encodings. These architectural choices improve training efficiency and model quality.

The LLaMA family includes models of various sizes, from 7 billion to 70 billion parameters, allowing researchers to choose a model that fits their computational resources. The availability of these models has sparked a wave of innovation, with researchers fine-tuning LLaMA for specific domains and applications.

BERT: Bidirectional encoder representations

While GPT and LLaMA are primarily generative models, BERT represents a different approach. BERT is an encoder-only model designed for understanding rather than generation. Unlike autoregressive models that only look at previous context, BERT is bidirectional—it considers both left and right context when processing each word.

BERT is pre-trained using two objectives: masked language modeling (randomly masking words and predicting them from context) and next sentence prediction (determining if two sentences follow each other logically). This training makes BERT excellent for tasks like question answering, sentiment analysis, and text classification.

However, BERT’s architecture makes it less suitable for text generation. You can’t simply sample from BERT like you can from GPT. Instead, BERT is typically used as a feature extractor, producing rich representations that downstream models or classifiers use for specific tasks.

Other notable foundation models

The landscape of large language models extends far beyond these three. T5 (Text-to-Text Transfer Transformer) frames all NLP tasks as text-to-text problems, using an encoder-decoder architecture. PaLM (Pathways Language Model) explores extreme scaling and multi-task learning. Claude, developed by Anthropic, emphasizes safety and alignment. Mistral has gained attention for its efficient architecture and strong performance at smaller scales.

Each model makes different architectural choices and training decisions, reflecting different priorities around performance, efficiency, safety, and openness. This diversity drives innovation and ensures that LLM technology continues to evolve rapidly.

4. Training and working with large language models

The pre-training process

Training a large language model from scratch is a massive undertaking requiring enormous computational resources. Pre-training typically involves processing trillions of tokens from diverse sources: books, websites, academic papers, code repositories, and more. The training data must be carefully curated to ensure quality and diversity while avoiding harmful content.

The training objective for most generative LLMs is straightforward: given a sequence of tokens (x_1, x_2, …, x_n), maximize the probability of predicting the next token:

$$ \mathcal{L} = -\sum_{i=1}^{n} \log P(x_i | x_1, x_2, …, x_{i-1}) $$

This cross-entropy loss is computed across billions of examples, gradually adjusting the model’s billions of parameters to minimize prediction error. Modern training runs might take weeks or months on clusters of thousands of GPUs or TPUs, costing millions of dollars.

Fine-tuning and instruction following

After pre-training, models often undergo fine-tuning to specialize them for particular tasks or to improve their instruction-following abilities. Instruction fine-tuning involves training the model on examples of instructions paired with appropriate responses. This teaches the model to behave as a helpful assistant rather than simply continuing text.

Here’s a simple example of how you might fine-tune a pre-trained model using Python and the Hugging Face Transformers library:

from transformers import AutoModelForCausalLM, AutoTokenizer, Trainer, TrainingArguments

from datasets import load_dataset

# Load pre-trained model and tokenizer

model_name = "meta-llama/Llama-2-7b-hf"

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained(model_name)

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_name)

# Load your fine-tuning dataset

dataset = load_dataset("your_instruction_dataset")

# Tokenize the dataset

def tokenize_function(examples):

return tokenizer(examples["text"], padding="max_length", truncation=True)

tokenized_dataset = dataset.map(tokenize_function, batched=True)

# Set up training arguments

training_args = TrainingArguments(

output_dir="./results",

num_train_epochs=3,

per_device_train_batch_size=4,

gradient_accumulation_steps=4,

learning_rate=2e-5,

warmup_steps=500,

logging_steps=100,

save_steps=1000,

)

# Create trainer and fine-tune

trainer = Trainer(

model=model,

args=training_args,

train_dataset=tokenized_dataset["train"],

)

trainer.train()

More advanced techniques like reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) further refine model behavior. In RLHF, human raters score different model outputs, and these preferences train a reward model. The LLM then uses reinforcement learning to maximize this learned reward, aligning its outputs with human preferences.

Prompt engineering and inference

Once an LLM is trained, interacting with it effectively requires prompt engineering—crafting inputs that elicit desired outputs. Well-designed prompts provide clear instructions, relevant context, and examples of the desired format.

For instance, consider asking an LLM to extract information from text. A poorly designed prompt might simply say “Extract names.” A well-engineered prompt would be more specific:

prompt = """

Extract all person names from the following text and format them as a JSON list.

Text: "Sarah Johnson met with Dr. Michael Chen and Professor Emily Rodriguez

to discuss their research findings."

Output format: {"names": ["Person Name 1", "Person Name 2", ...]}

Answer:

"""

# Using the model for inference

from transformers import pipeline

generator = pipeline('text-generation', model='gpt2-medium')

response = generator(prompt, max_length=200, num_return_sequences=1)

print(response[0]['generated_text'])

Advanced prompting techniques include few-shot learning (providing examples in the prompt), chain-of-thought prompting (asking the model to show its reasoning), and retrieval-augmented generation (providing relevant documents as context).

Challenges in LLM deployment

Deploying large language models in production presents several challenges. First, inference is computationally expensive—running a 70-billion-parameter model requires substantial hardware. Techniques like quantization (reducing precision of model weights), distillation (training smaller models to mimic larger ones), and prompt caching help manage these costs.

Second, LLMs can produce incorrect or biased outputs. They might confidently state false information (hallucination) or reproduce biases from training data. Production systems must include safeguards like fact-checking, output filtering, and human oversight for high-stakes applications.

Finally, latency matters for user experience. Users expect near-instant responses, but generating text token-by-token can be slow. Optimizations like speculative decoding, parallel sampling, and efficient inference engines help reduce latency.

5. Applications and capabilities of LLMs

Natural language understanding and generation

The most obvious application of large language models is generating human-like text. LLMs power chatbots, content creation tools, email assistants, and creative writing applications. They can adjust their tone, style, and complexity based on context, making them versatile writing partners.

Beyond generation, LLMs excel at understanding and analyzing text. They can summarize long documents, translate between languages, answer questions based on provided context, and extract structured information from unstructured text. For example, an LLM could read thousands of customer reviews and generate a comprehensive summary of common themes and sentiments.

Code generation and programming assistance

One of the most impactful applications has been in software development. LLMs trained on large code repositories can generate code from natural language descriptions, explain existing code, debug errors, and suggest completions. Tools built on LLMs have become essential programming companions for many developers.

Here’s an example of how an LLM might help with code generation:

def analyze_sentiment(text):

"""

Analyzes the sentiment of input text using a simple approach.

This function could be generated by an LLM when given a prompt like:

"Write a Python function that analyzes text sentiment and returns

a score between -1 (negative) and 1 (positive)."

"""

import re

from textblob import TextBlob

# Clean the text

cleaned_text = re.sub(r'[^a-zA-Z\s]', '', text.lower())

# Analyze sentiment

blob = TextBlob(cleaned_text)

sentiment_score = blob.sentiment.polarity

# Classify sentiment

if sentiment_score > 0.1:

category = "positive"

elif sentiment_score < -0.1:

category = "negative"

else:

category = "neutral"

return {

"score": sentiment_score,

"category": category,

"text": text

}

# Example usage

result = analyze_sentiment("I absolutely love this product! It's amazing!")

print(f"Sentiment: {result['category']} (score: {result['score']:.2f})")

Knowledge work and reasoning

LLMs are increasingly used for tasks requiring reasoning and knowledge synthesis. They can help with research by summarizing papers, identifying relevant literature, and explaining complex concepts. In business contexts, they analyze data, generate reports, and provide decision support.

Interestingly, large language models exhibit some reasoning capabilities not explicitly taught. They can solve novel problems by breaking them into steps, apply logical rules, and even perform basic mathematical reasoning. While not perfect, these emergent abilities make LLMs valuable for knowledge-intensive tasks.

Multimodal applications

Modern LLMs are expanding beyond text. Vision-language models can understand images and generate descriptions, answer questions about visual content, or even generate images from text descriptions. Audio-language models can transcribe speech, generate voices, or understand audio context.

This multimodal capability opens exciting applications: accessibility tools that describe visual content to visually impaired users, educational systems that combine text, images, and explanations, or creative tools that let users design using natural language.

6. Limitations and future directions

Current limitations of language models

Despite their impressive capabilities, large language models have significant limitations. They sometimes produce plausible-sounding but incorrect information—a phenomenon called hallucination. They lack true understanding and can be fooled by adversarial inputs that humans would easily recognize as nonsensical.

LLMs also struggle with tasks requiring precise calculation, logical consistency over long chains of reasoning, or up-to-date information beyond their training cutoff. They can exhibit biases present in training data, potentially amplifying societal prejudices. Privacy concerns arise because LLMs might inadvertently memorize and reproduce sensitive information from training data.

Resource consumption is another limitation. Training large models requires massive computational resources, raising environmental and accessibility concerns. Not every organization can afford to train or even run the largest models, potentially creating an AI divide.

Safety and alignment challenges

Ensuring that LLMs behave safely and align with human values remains an active research area. Models might generate harmful content, provide dangerous instructions, or be manipulated to bypass safety measures. Researchers work on techniques like red-teaming (testing models with adversarial inputs), constitutional AI (training models with explicit principles), and interpretability (understanding why models produce particular outputs).

The alignment problem becomes more critical as models become more capable. A highly capable model that misunderstands human intentions or values could cause significant harm, even without malicious intent. This has motivated research into robust alignment techniques that scale with model capability.

Future developments in LLM technology

The field of large language models continues to evolve rapidly. Several trends are likely to shape future development:

Efficiency improvements: Researchers are developing more efficient architectures and training methods that deliver better performance with fewer parameters and less computation. Techniques like sparse models, mixture of experts, and improved training algorithms promise to make powerful LLMs more accessible.

Better reasoning and factuality: Future models will likely incorporate explicit reasoning modules, retrieval mechanisms for up-to-date information, and verification systems to reduce hallucinations. Hybrid systems that combine LLMs with structured knowledge bases or symbolic reasoning engines show promise.

Specialized and domain-specific models: While general-purpose LLMs are incredibly versatile, we’ll likely see more specialized models optimized for specific domains like medicine, law, or scientific research. These models will balance broad capabilities with deep expertise in their domains.

Improved interpretability: Understanding how LLMs arrive at their outputs remains challenging. Future research will likely provide better tools for interpreting model decisions, debugging unexpected behaviors, and ensuring transparency—critical for high-stakes applications.

Longer contexts and better memory: Current models have limited context windows, restricting how much text they can consider at once. Future models will likely handle much longer contexts or incorporate explicit memory systems, enabling them to work with entire books, codebases, or conversation histories.

7. Conclusion

Large language models represent a fundamental breakthrough in artificial intelligence, enabling machines to work with human language in unprecedented ways. From the transformer architecture that powers them to the diverse applications they enable, LLMs have rapidly become essential tools across industries. Models like GPT, LLaMA, and BERT each bring different strengths, whether for generation, understanding, or specialized tasks. As foundation models continue to evolve, they promise to reshape how we interact with information, create content, and solve complex problems.

The journey of LLM development is far from over. While current models have impressive capabilities, they also face important limitations around accuracy, reasoning, efficiency, and safety. Ongoing research addresses these challenges while pushing the boundaries of what’s possible. Whether you’re a researcher, developer, or simply someone interested in AI, understanding large language models provides crucial insight into one of the most transformative technologies of our time. As these systems continue to improve and new architectures emerge, they will undoubtedly play an increasingly central role in shaping our technological future.

8. Knowledge Check

Quiz 1: Defining Large Language Models

Question: Explain what the term “large” in Large Language Model (LLM) refers to and describe the fundamental task an LLM performs at its core.

Answer: The term “large” describes two key aspects. First, it refers to the enormous training dataset. Second, it indicates the model’s size in billions of parameters. Fundamentally, an LLM predicts the next word in a text sequence. It analyzes previous words to make these predictions.

Quiz 2: The Transformer Revolution

Question: What was the primary limitation of pre-transformer models like Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), and how did the transformer architecture overcome this challenge?

Answer: RNNs had a major flaw: they processed text sequentially. This made them slow. Additionally, they struggled with long-range text dependencies. In contrast, transformers process entire sequences simultaneously. Furthermore, they use self-attention mechanisms. This helps them identify relevant word relationships regardless of position.

Quiz 3: The Self-Attention Mechanism

Question: Using the example sentence “The animal didn’t cross the street because it was too tired,” explain how the self-attention mechanism determines what the word “it” refers to.

Answer: Self-attention computes attention scores between words. In this sentence, it creates high scores between “it” and “animal.” Therefore, the model determines that “it” refers to “animal.” The mechanism uses learned patterns to identify these contextual relationships.

Quiz 4: Model Training Lifecycle

Question: Describe the two primary phases in the lifecycle of a modern LLM and explain the objective of each phase.

Answer: Modern LLMs undergo two training phases. First, pre-training exposes the model to massive text corpora. This builds general language understanding through self-supervised learning. Next, fine-tuning adapts the model to specific tasks. It uses smaller, targeted datasets. This approach demonstrates transfer learning in action.

Quiz 5: Differentiating Major Models

Question: Contrast the primary architectural approach and main purpose of the GPT family of models with that of BERT.

Answer: GPT uses a decoder-only architecture. It generates text autoregressively, one token at a time. Therefore, GPT excels at creative writing and generation tasks. Conversely, BERT employs an encoder-only design. It processes text bidirectionally, analyzing both left and right context. Consequently, BERT performs better on classification and sentiment analysis tasks.

Quiz 6: The Art of Prompt Engineering

Question: What is prompt engineering, and why is it essential for interacting effectively with a trained LLM?

Answer: Prompt engineering crafts specific inputs to guide LLM outputs. It provides clear instructions and relevant context. Moreover, it includes examples of desired formats. As a result, well-designed prompts produce more accurate responses. This makes prompt engineering essential for effective LLM interaction.

Quiz 7: Challenges in LLM Deployment

Question: Identify and describe two significant challenges associated with deploying large language models in a production setting.

Answer: LLM deployment faces two major challenges. First, inference requires substantial computational resources and expensive hardware. Second, models can hallucinate and generate false information. Additionally, they may reproduce training data biases. Therefore, production systems need fact-checking safeguards and human oversight.

Quiz 8: Advanced LLM Capabilities

Question: Besides generating human-like text, what has been one of the most impactful applications of LLMs in the software development field?

Answer: Code generation represents LLMs’ most impactful software development application. These models train on large code repositories. Consequently, they can generate code from natural language descriptions. Furthermore, they explain existing code and debug errors. They also suggest code completions. Thus, they become essential developer tools.

Quiz 9: Core Limitations and Risks

Question: What is “hallucination” in the context of LLMs, and why does this phenomenon represent a significant limitation?

Answer: Hallucination occurs when LLMs produce plausible but incorrect information. This represents a critical limitation. Moreover, models cannot access information beyond their training cutoff. Additionally, adversarial inputs can fool them. They may also reproduce harmful biases from training data. Therefore, hallucination poses significant risks for practical applications.

Quiz 10: The Alignment Problem

Question: What is the “alignment problem” in LLM research, and what is one advanced technique used to mitigate it?

Answer: The alignment problem ensures LLMs behave safely and follow human values. Researchers use red-teaming to address this challenge. This technique tests models with adversarial inputs. Consequently, it helps discover potential safety flaws. Then, developers can fix these issues before deployment.